Ypres in the Great War of 1914-1918

7 October 1914: The German Army Arrives in Ypres

On one day of 7 October 1914 about 8,000 cavalrymen and soldiers of an Imperial German cavalry division arrived in Ypres. They ordered thousands of loaves of bread to be baked, left bewildered shopkeepers with payment in German coins and notes or pre-printed German coupons for food, drink and other goods, and requisitioned hay for the horses. The Staff officers emptied the town's coffers of about 62,000 Francs and left the following day, having “passed through” Ypres. Apart from some accounts of stealing and damage no fighting, killing, sabotage or reprisals are believed to have taken place during this brief visit.

14 October 1914: The British & French Arrive in “Wipers”

|

The first British soldiers to arrive in Ypres were men of the IV Corps under General Rawlinson (7th Division and 3rd Cavalry Division) on 14 October 1914. There they made contact with French troops of 87th Territorial Division who were already in the town. The British Official History states that the inhabitants were carrying on very much as usual. The British 7th Division was very tired by a two-day march from Ghent on pavé (cobbled) roads and were billeted amongst the locals' houses to get some rest.

The British Corps Commander put up an outpost line covering the east of the town. The task was to defend the town and to block the route for the German Army through Ypres to the ports on the French and Belgian coast.

Soldiers in the British Army quickly turned the French name of Ypres into a much easier word to pronounce. They called it “Wipers”. The British Army remained in “Wipers” for four years from October 1914 to the end of the war in November 1918.

Allies Block a German Return to Ypres

|

As events developed at that time with the so-called “Race to the Sea”, within three weeks of the German Army's brief visit to Ypres on 7 and 8 October 1914 the Germans had to carry out a major offensive operation, very costly in German casualties, to try to make their way back into Ypres.

The First Fight for Ypres, Autumn 1914

The First Battle of Ypres (19 October - 22 November 1914) began to the east and south east of the city in mid October 1914. It was the first of many long battles during the Great War to hold or win possession of this ancient city and it's strategic route to the French and Belgian coastal ports.

Although outnumbered, the British soldiers held their line against the odds. The British defence east of Ypres, including a crucial, successful counter-attack at Gheluveld on 31 October 1914, was the final phase in the “Race to the Sea”, putting a stop to the possible return of the German Army into Ypres before the onset of the winter weather.

With the defence of Ypres blocked by the British, and with the situation on the German Army's Western battlefront quickly turning from a war of movement into a static situation of siege warfare, the senior German commanders must have bitterly regretted having once been in possession of Ypres and having voluntarily left it.

German Attempts to Capture Ypres

|

The town would become the focus of German attention to recapture it over the next three years. The German Army carried out major offensive operations in an attempt to gain possession of the town in the autumn of 1914, the spring of 1915 and the spring of 1918. The British carried out two major offensives to push the Germans off the dominating high ground around the north, east and south of the town in 1917.

During the massive operation of the 1918 German Spring Offensive (“Operation Georg” at Ypres) the German Army advanced to within a few kilometres east of Ypres, but was still not successful in capturing it. Marker stones, known as Demarcation Stones or Bornes du Front, were put up as a private project after the war to show the extent of the German advance into Belgium and France.

The city never fell into German hands during the war.

Holding the Strategic Landmark

|

The defence of Ypres, or “Wipers”, was key to the British hold on this sector of the Western Front. The town was an important strategic landmark blocking the route for the Imperial German Army through to the French coastal ports. According to the British Official Military History, the danger of the Allied line being broken and rolled up at Ypres in October and November 1914 was “one of the most momentous and critical of the war, and only by the most desperate fighting did the Allies succeed in maintaining their front. Had they given ground on the scale they did after the Battle of the Frontiers in August 1914, or even in March and April 1918, the whole of Belgian territory must have been lost, and the Germans would have reached Dunkirk and Calais — which were, indeed, their objectives. If these ports had fallen to the enemy the effect on our sea communications and on operations generally might well have proved fatal not only to the British Empire, but to the whole of the civilized world.” (MO)

Many thousands of Allied troops died to maintain the Allies' possession of this place. They died in the rubble of its buildings and the shattered farmland around it, fighting in ferocious battles and surviving daily life in inhuman conditions.

On the German side of the wire, many thousands of German lives were also lost in the landscape north, east and south of Ypres during the German Army's four years of offensive and defensive battles.

Civilians in Ypres

Up until the spring of 1915 most of the civilian population, which numbered about 18,000 in 1914, continued to live in and around the town. With the sudden arrival of hundreds of French and British soldiers in the autumn of 1914 it soon became a busy hub for the military forces passing through it or spending time out of the line from the battle areas to the north, east and south of the city. The cafés and shops were busy with troops. A British Army Town Major was responsible for liaison between the civilian authorities and the military.

German artillery shells had been fired at the town from mid November 1914. Some 10 to 20 shells were said to have landed on the town every minute. The population took shelter in the cellars, in the ramparts and the bombproof shelters at the infantry barracks. In the following months the shelling was not constant over the winter of 1914/1915. Most of the local population were determined to stay in their town.

Civilians Evacuated, May 1915

|

From mid April 1915 there was an increase in the severity of German artillery shelling and aerial bombing onto the town. The shelling not only caused destruction of buildings and seriously endangered civilians sheltering in them, but the constant damage to the drainage and sewerage system made it irrepairable and unsanitary. There was sickness amongst the people due to the poor living conditions.

Although the shopkeepers and cafe owners had kept their businesses going as far as they could, the severity of the shelling onto the town by 21 April resulted in people deciding to close down and leave. The German trial of a chlorine gas cloud as a war weapon on 22nd April was released against two French divisions in the northern sector of the Ypres Salient. At that time local people were still living in farms and villages very close behind the Front Line. Witness accounts from the first release of the gas cloud tell of civilians being caught up in the terror of the experience, taking shelter in their farms, arriving at Poperinge with symptoms of chlorine gas poisoning and being removed from the battle area by the German Army.

In May 1915 it was decided to evacuate the remaining civilians from Ypres who had wanted to stay in their town. The last to leave was the mayor, Monsieur Colaert. Taking what they could carry, many of them either walked, were put on trains from Ypres or Vlamertinge station or were helped on their way in army lorries in the direction of Poperinge.

Civilian Casualties of 1914-1918

A memorial in Ypres opposite the western end of the Cloth Hall commemorates the civilians killed during the 1914-1918 war in and around Ypres.

Ramparts and Fortifications

|

The history of Ypres up to 1914 records how the city was attacked and besieged over the centuries. Following a period of peace for Ypres after the founding of the Belgian nation in 1830, the surviving defensive ramparts on the eastern and southern sides of the town once more took on the role of fortified, defensive strongpoints to protect the city from an invader.

The tunnels, passageways, rooms and casemates built into the ramparts and bastions by the French military engineer Sébastien Le Prestre, Seigneur de Vauban (1633-1707), during the French occupation in the 1680s, were used by French and British troops as shelters, accommodation, medical dressing stations and headquarters from October 1914.

The infantry barracks in the west side of the city had deep cellars, thick walls and could offer good protection from artillery shelling. The rooms and casemates around the Rijselpoort (Lille Gate) provided secure bombproof rooms for headquarters and accommodation.

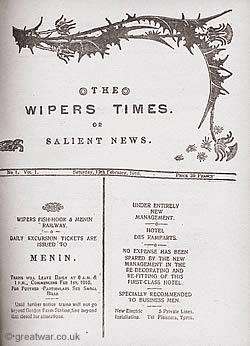

“The Wipers Times”

|

In early 1916 one of the British units, the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment), was holding the Front Line at Hooge in the Ypres Salient. The regiment's rear headquarters and billets was in Ypres in what the men described as rat-infested, waterlogged cellars. Finding a printing press, paper and most of the type (letters) in a building near the market square, some of the officers and men of the Sherwood Foresters, including a former editor, decided to set it up to print pages with anything that came into their heads.

The editorial “den” for about three months was in the casemates built by Vauban in Ypres' eastern ramparts. 100 copies of the first issue of what they called “The Wipers Times or Salient News” were printed on the press near the Cloth Hall, dated Saturday 12 February 1916. They produced the pages while out of the line after a night spent in the trenches on a working party, and during “quiet” periods when the German artillery shells weren't raining down on the town. “The Wipers Times” contained witty articles, poems and “adverts” referring to the awful circumstances of the war they found themselves in, the dangerous conditions they faced daily, but put across with a sense of humour and tongue-in-cheek. Clever text is written with good humour and illustrates well the tradition in which the British soldier has used his sense of humour to get him through very dark and difficult times.

A second issue of “The Wipers Times” (200 copies) was printed on the printing press by the Cloth Hall, but after a German 5.9 inch shell landed on the building and the printing press, the Sherwood Foresters managed to find another printing press near “Hellfire Corner”. They moved it behind the lines to print the next two issues from Ypres. A further 11 issues were printed during the war from the Salient and the Somme battlefronts.

The Military in Ypres

|

During the four years that the British Army was holding the Ypres Salient thousands of British troops spent time in Ypres or passed through it. They were either based in the town as part of a rear headquarters, running supply, pioneer, engineering and transport depots, or they were billeted in the town cellars and ramparts while out of the Front Line sector. Some would pass through it on their march from the rear areas west of Ypres, passing through the city on their way to the Allied Front Line in the Ypres Salient battlefields. Many hundreds would never make the return journey.

Activity by Day and Night

In the early years of the war, 1915 and 1916, accounts by soldiers describe how the town was busy in the day but that it gave the appearance of being deserted at night. An account by “The Padre” in the first issue of “The Wipers Times” describes the daytime scene in Ypres in February 1916:

“Transports and troops pass and re-pass along the ruined streets. From almost every aspect, through gigantic holes torn in the intervening walls, the rugged spikes of the ruined cathedral town mark the centre of the town.” (1)

The Padre goes on to describe how the town became deserted at night when the soldiers had gone up to the Front Line area to carry out working parties or as reliefs:

“But at night all is different. The town is well-nigh deserted. All its inhabitants, like moles, have come out at dusk and have gone, pioneers and engineers, to their work in the line. Night after night they pass through dangerous ways to more dangerous work. Lightly singing some catchy chorus the move to and fro across the open road, in front of the firing line, or hovering like black ghosts, about the communication trenches, as if there were no such thing as war. The whole scene lights up in quick succession round the semi-circle of the salient as the cold relentless star-shells sail up into the sky.” (2)

|

According to Veterans of the Ypres Salient, later in the war most movement by troops was carried out during the hours of darkness. Veterans have recounted how the shattered town was quiet with troop movement during daylight hours. This was likely due to the increase in enemy aerial activity by 1917. After darkness had fallen, however, the town and the surrounding area behind the British Front Line came alive with thousands of men, horses and wagons moving about to carry out reliefs for troops in the line or carry forward supplies and ammunition. WW1 Veterans also used to say that the winter months were preferable to the soldiers, in spite of the bad weather, because the long winter nights provided them with more hours of darkness and the protection from being seen by the enemy.

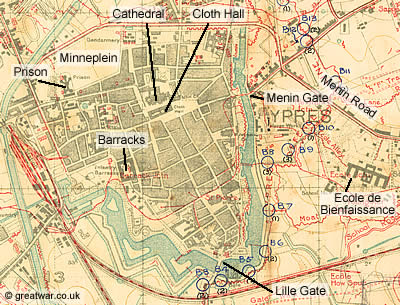

Menin Gate and Lille Gate

Two of the access routes in and out of the town on the east and south side of the city became very familiar to the British military units in the Ypres Salient.

Menin Gate

Taking the route from Ypres leading in the direction of Menin on the east side of the city, the soldiers would pass through the gap in the old raised ramparts where the originally named town gate called the Hangwaertpoort, Meensepoort or Porte de Menin had been located. For most of the four years when the Front Line east of Ypres was stabilized about 4 kilometres east of Ypres this route would take them into the battlefield zone to the north-east at Wieltje and east to Hooge on the Ypres Salient battlefields.

The route to Hooge along what the troops called “The Menin Road” became one of the most famous and dangerous places for the British to move about on the Western Front. A crossroads and railway crossing about 2 kilometres due east of Ypres on the Menin Road became known as “Hellfire Corner”. This was due to the fact that the Germans had a view of it from their positions on the higher ground further east and, as a major road route for the British into the Salient, the Germans shelled it constantly. The Menin Gate, the Menin Road and Hellfire Corner are three names bound together in the British Military History of the Great War at Ypres.

The Lille Gate

The access route to and from Ypres in the south of the city was very well used by troops making their way to and from the battlefields of the Ypres Salient. This gate was called the Rijselpoort and was the only one of the numerous formal town gates that had survived over the centuries in the form of an actual gateway.

The Destruction of Ypres

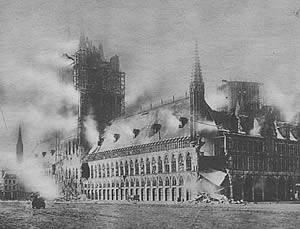

First Artillery Damage: November 1914

|

German artillery fired continuously onto the town of Ypres from mid November during the First Battle of Ypres (19th October - 22nd November 1914). The shells set fire to buildings in numerous places. The German artillery fired incendiary shells onto the city from positions to the north-east, east and south-east of Ypres. The first serious damage to the buildings of Ypres occurred on 22nd November 1914. Two of Ypres' most famous historic buildings, St Martin's Cathedral and the Cloth Hall (Lakenhalle) were set on fire by incendiary shells. Scaffolding on the belfry caught fire; ironically this was on the building because it had been undergoing refurbishment of the stonework which was almost complete when the war broke out.

Intense Bombardment: April 1915

A few months later in mid April 1915 an intensive, deliberate German bombardment started up onto the buildings of Ypres. There was increased activity by German planes bombing Ypres and Poperinge. There was also the arrival of long range, heavy German guns. These guns included a huge 42cm howitzer hidden in the Houthulst Forest to the north of the town. This huge gun was nicknamed “Dicke Bertha” by the German Army. This nickname translates as “big” or “large” Bertha. Consequently the gun soon became known as “Big Bertha” to the troops of the British Army. Accounts by soldiers say that the shell could be seen, it was so large, and that it sounded like a steam train rushing through the air.

Although the Cloth Hall had lost its roof for some weeks already the walls were still standing and, up to this point in time, it was used as billeting accommodation for about 1,500 men, the equivalent of two British battalions. But the shelling in late April caused too much danger for this and the building was evacuated by the British.

The bombardment in April 1915 was the prelude to the launch of a German trial gas attack on the Allied Front Line in the Ypres Salient on 22 April 1915. It was the beginning of the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April - 8 May 1915) and the beginning of the total destruction of one of the most beautiful cities in Flanders.

By the end of the Second Battle of Ypres the British Engineers of Second Army were constructing strong-points on the Ypres ramparts as part of a Third Defensive Line. This was called the “Canal Line” and it was located behind the forward defensive lines of the Front Line, the G.H.Q. Line, and the Second Line. The Canal Line ran around the north, east and south of Ypres, constructed from the Brielen Bridge on the Ieper-Ijser (Ypres-Yser) canal, at the boundary of the British and French Armies, along the eastern canal bank, around the eastern ramparts of Ypres and joined the Ypres-Comines canal south of Ypres.

Not all the damage to buildings was caused by the German artillery, however. The British Engineers blew down the tower of St. Jacob's church located near the eastern ramparts because it was being used by German artillerymen to range their targets on Ypres.

Later in the summer of 1915 an incident occurred with great loss of life when a group of about 40 men of the 6th Battalion Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry (D.C.L.I.) were buried alive in the cathedral vaults. An intensive German bombardment shattered the ceilings of the vaults and 22 of the men could not be dug out alive and they died on that day. Their graves are close together in the Ypres Reservoir Cemetery in Ypres.

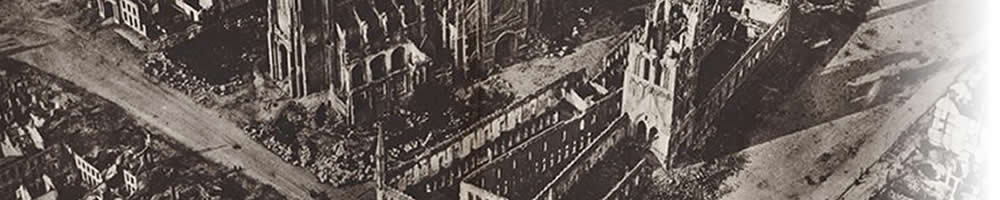

A Shattered City: 1917 & 1918

|

During 1917 and 1918 the city was continuously shelled by German artillery. By the end of the war there was no building left untouched. Only a tiny number of buildings, walls or façades were still intact. These included the post office in the Rijselstraat, the Biebuyck House in the Diksmudsestraat and a row of terraced façades in the d'Hondtstraat. The medieval town with its historic buildings, centuries of traditions and its pre-war prosperity had been demolished.

Sacrifice and Memories

The memory of so much bloodshed, on all sides, is inextricably entwined with the name of Ypres.

These words were attributed to “The Padre” in the first edition of “The Wipers Times” soldiers' newspaper printed in Ypres in February 1916. He could not have foreseen that the war would last another two and a half years, and that even more destruction and death would take place in the city in that time. His thoughts in 1916 must indeed have reflected the feelings of many British servicemen who spent time in and around Ypres in the war, wondering about the day when war was over and normal life had resumed, that the sacrifice and memories of those who gave their lives in her defence would still live on:

“Ypres has died but shall live again. Her name in the past was linked with kings; but to-morrow she will have a nobler fame. Men will speak of her as the home of the British soldier who lives in her mighty rampart caverns or in the many cellars of her mansions. And even when the busy hum of everyday life shall have resumed its sway in future days, still there will be heard in ghostly echo the muffled rumbling of the transport, and the rhythmic tread of soldiers' feet.” (3)

Daily Last Post Ceremony in Ypres

|

The people of Ypres have not forgotten the loss of the civilians and military men and women in Ypres and the Ypres Salient. A daily ceremony of Remembrance at the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres has been carried out since 1929 without interruption except for the period of German occupation in World War Two.

Last Post Ceremony at the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing

Reconstruction of Ypres

Continue the story of Ypres and the Great War of 1914-1918 with the huge task of rebuilding the shattered city:

Next >> Reconstruction of Ypres from 1919

Further Reading

Ypres in War and Peace

by Martin Marix Evans

Published by Pitkin Guides, English edition (June 1992); ISBN-10: 0853726108 & ISBN-13: 978-0853726104

The Wipers Times: The Complete Series of the Famous Wartime Trench Newspaper (hardcover)

by Malcolm Brown (Editor)

Forward by Ian Hislop. 400 pages. Published by Little Books Ltd (16 Jan 2006); ISBN-10: 1904435602; ISBN-13: 978-1904435600

The Riddles of Wipers: An Appreciation of the Trench Journal “The Wipers Times” (paperback)

by John Ivelaw-Chapman

176 pages. Published by Pen & Sword Military (21 Jan 2010). ISBN-10: 1848841914; ISBN-13: 978-1848841918

Film

The Pathe Collection -The Battle of Ypres (DVD)

Format: PAL. Regions: All. (Release 8 November 2010); ASIN: B0045U3B0W

Short Films about “The Wipers Times”

Watch a series of 10 short films compiled by Visit Flanders, featuring Ian Hyslop, producer of the 2013 drama Wipers Times.

YouTube: www.youtube.com The Wipers Times

Related Topic

Battles of the Ypres Salient

Acknowledgements

(GWPDA) Photographs and header photograph detail with grateful thanks to the Great War Primary Document Archive: Photos of the Great War.

(OS) Courtesy of Ordnance Survey, The Battles of Ypres 1917 Map, dated 1919.

(MO) Military Operations: France and Belgium 1914 Volume II, p. 126-127

(1), (2) and (3) The Wipers Times or Salient News, No. 1, Vol. 1. Saturday 12 February 1916.

(4) Photograph from a private collection.

(5) Detail from an original photo of Last Post Association Buglers, courtesy of the Ieper Tourist Office, Stad Ieper: copyright Tijl Capoen.